What do you do?

This is a question I get with regularity. Sometimes it is related to health, be it diet, exercise, or the combination of the two. Sometimes it is related to work, productivity, or my routine(s). Regardless of the focus, the question itself has always been one that bothers me.

For most of the time I have been receiving the question, and have been dodging it for the most part, I thought my reluctance to answer was driven by my belief that it didn’t matter what I did/do. What matters is what you do going forward. What I have working for me might be right for you, but then again it might not be. Why try and create a carbon copy of my life in your own? What works for me isn’t guaranteed to work for you. For all our similarities, we remain individuals, with our own mindsets, physiologies, personal microbiomes, circumstances, and more.

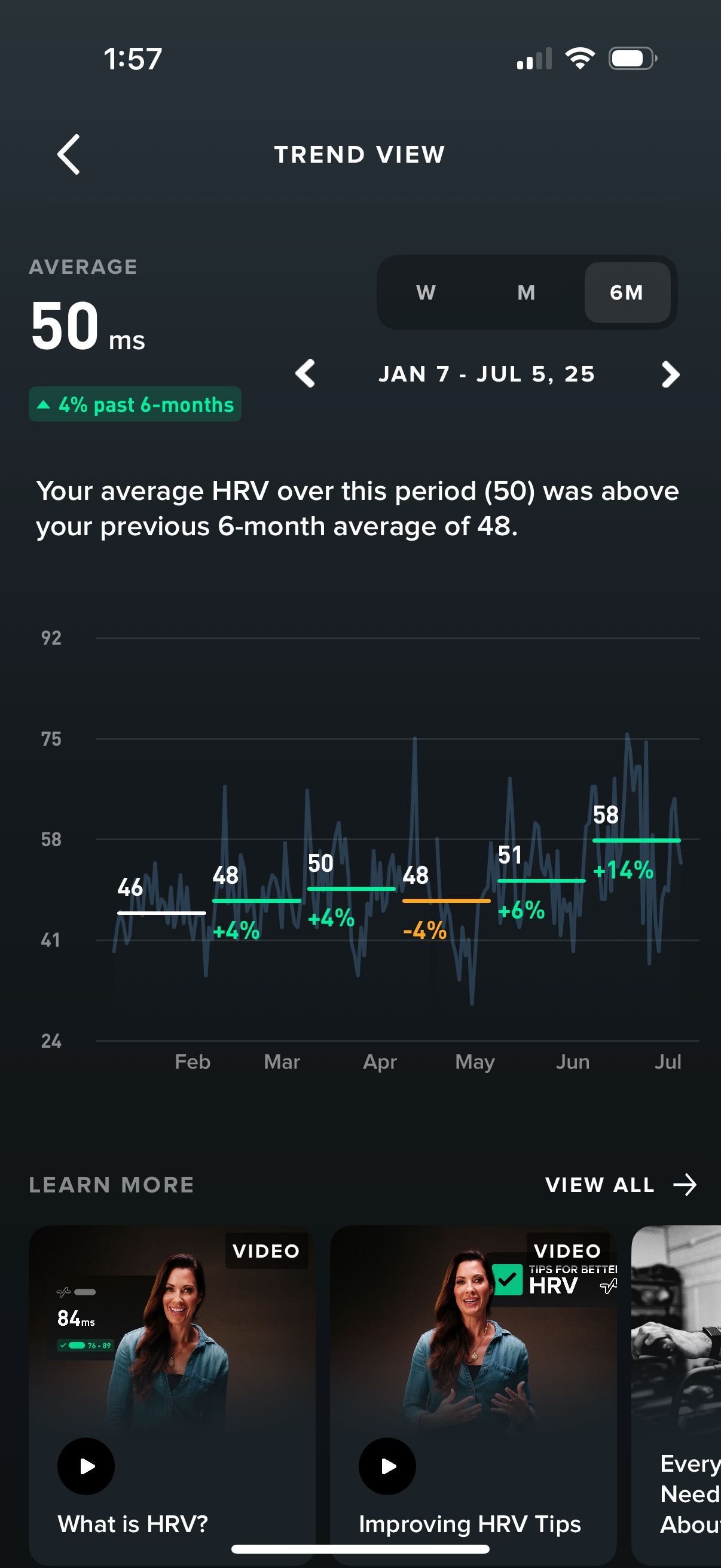

As I continued to receive the question repeatedly, I began to realize another reason I shy away from giving a straightforward answer. This is because what I do is not constant. This is intentional. I am constantly experimenting. For example, as I write this, I am three weeks into an entirely new workout regimen. How helpful would it be for me to tell you what I am doing if neither of us yet knows if it is “good” or not for me, much less you? And this isn’t just for exercise. I am also eight months in to going mostly plant based in my diet (NOTE: Katy tells me I can’t be “weird” so when we are at a friend’s house for dinner, I eat whatever they put in front of me). I take time to reassess my calendar, and thus routines, on a quarterly basis at a minimum. Asking me what I “do” seems to try and fix us both into a point in time that I sincerely believe will not serve either of us.

A recent conversation with my college roommate highlighted yet a third reason I believe these questions are misguided. He is in incredibly good shape, and his work colleagues ask him the same question. His point is that he cannot provide a simple answer as what they are seeking is less what he does today, and more how to be what he is today in terms of body composition. “That,” he points out, “is the result of years of compounding factors, diet, sleep, exercise, and more. If I gave you what I do right now, it is unlikely it would work like you expect. It is a process.” I couldn’t agree more.

For me, then, the question, or rather the question(s) behind the question really are of three kinds:

1. Basic curiosity on what I am (or someone else is) doing at a point in time

2. Outcome focused, i.e., how can I get the results you have?

3. Process focused, i.e., how do you go about testing, assessing, and iterating as a methodology rather than a point in time implementation of something specific?

Each of these are very different and would lead the interrogator down an entirely different path. The why behind the question matters. If just curious as to what someone else “does” to create some small talk, that is one thing. If desirous of achieving someone else’s results, besides that being a fool’s errand in my mind (comparison is the thief of happiness), I believe you are still better off focusing on #3 (process), rather than #2 (outcome).

This is because there is always room for improvement. It is also because our bodies and minds change over time, and we need to adapt and change with them. It is often said that if you always do what you have always done then you will always be what you have always been. With our mind and body, this isn’t actually true. For example, our metabolism slows 1% on average each year after we turn 30. If we do what we have “always done” on diet and exercise, we will not end up being what we have always been, but rather end up being fatter and less fit versions of ourselves of prior years. Thus, as the Red Queen informed Alice, “My dear, here we must run as fast as we can, just to stay in place.”

But in the end, maybe all of this is overcomplicating things. Not everyone wants to invest the time and mindshare to constantly experiment in their own lives. Many might not be looking for the exact process or even results of me or anyone else, but just the “shortcut” to get to a better place than they are today. In effect they are after the Pareto equilibrium: that thing that will get you to 80% of the way there with 20% of the work or effort.

This is real. In law school, several years out of competitive swimming, I found myself again eligible to swim for the university team in the UK because they didn’t have the same eligibility rules as the NCAA, where I had used up my four-years of eligibility. Years out of competitive shape, and training ~25% as much as I did when I was an NCAA swimmer, I was still able to go within a couple of seconds of my best times (i.e., 2% off in a 200-meter race). All that extra work was necessary for that last two percent, and what was required to compete at the highest levels. To get pretty close to those same results, though? That required a LOT less.

That is where simple rules of thumb can often suffice, like Dr. Andrew Huberman’s Tweet on diet and exercise. This won’t have you winning the Boston Marathon or any bodybuilding competitions, but for most of us, that isn’t the goal anyway. As with so much else, the answer is to be more thoughtful about why we are asking questions like this in the first place. What do we actually want? Without knowing where we want to go, it is unlikely we will ask the right questions, and receive the right answers, needed to get us there.